Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

Advertisement

Constanza Morén is coordinator of the Basic and Translational Research Laboratory in Schizophrenia, Institute of Neuroscience at IDIBAPS in Barcelona, Spain, and a professor in the Nursing Faculty at the University of Barcelona.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

You have full access to this article via your institution.

My father worked as an industrial engineer in the civil service and made a mean potato cake. He held my hand every day as he walked me to school, and taught me and my two sisters to ride bicycles in our hometown of Tarragona, Spain. My father, who died in 2023 at the age of 79, also lived with paranoid schizophrenia.

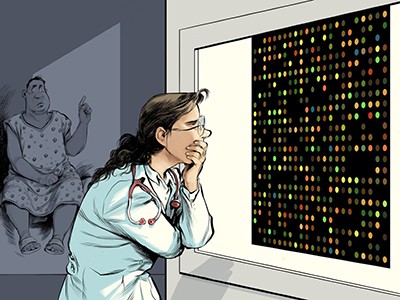

I might never know whether I’ve inherited a risk factor for this condition from him. But I do know that I share his stubbornness, which has enabled me to complete a PhD in biomedicine. Now, I help to coordinate the Basic and Translational Research Laboratory in Schizophrenia in Barcelona, Spain. My colleagues and I aim to understand the molecular basis of schizophrenia, and to assess experimental therapies that alleviate some of the symptoms, such as low motivation, that often go untreated.

My personal and professional experiences have convinced me that better communication and collaboration between the scientific community, health-care professionals and the public — including individuals affected by schizophrenia and their families — is urgently needed, to improve people’s lives.

Personalized profiles for disease risk must capture all facets of health

Personalized profiles for disease risk must capture all facets of health

Scientists still know very little about this complex disorder, the study of which is chronically underfunded. We don’t understand all of its biological underpinnings. We don’t have biomarkers to diagnose it. And treatments — which focus mainly on alleviating a subset of symptoms, including delusions and hallucinations — have long stagnated. One standard therapy, haloperidol, is more than 50 years old. It has side effects such as involuntary motor movements, tremors and impaired balance. More-recent antipsychotic drugs are associated with weight gain, metabolic syndrome, sexual dysfunction and more. In many cases, the side effects are so debilitating that people stop taking the medication.

Worse, people who have schizophrenia must also contend with the fact that society does not know how to help them. I saw this at first hand with my father.

At around 60 years old, he stopped taking haloperidol. But the tremors and impaired motor control that the drug had caused persisted. At the end of his life, he often fell, and other symptoms re-appeared. The paranoia caused by schizophrenia, along with a lack of self-awareness about his condition, meant that he would not seek help — so my sisters and I traipsed all over town to try to get it for him. We met with neurologists, social workers, civil servants, receptionists, nurses and psychiatrists. We heard the same message time and again: we could get help only if we asked a court to declare my father incapable of looking after himself. My father would have seen this ‘solution’, in my view, as a betrayal by the only people he trusted. Our family ruled it out from the start.

How can researchers help with societal problems such as this? First, they must step out of their silos and form collaborations with clinicians and community carers. Such multidisciplinary approaches are sorely lacking, owing to a seeming failure to recognize that each person with schizophrenia has unique needs. The disorder can be influenced by myriad biological factors, from genetics to alterations in neuronal development, as well as by chronic stress, traumatic experiences and drug use. Only when specialists in all these areas communicate can carers identify the best therapeutic approach for each person.

Male–female comparisons are powerful in biomedical research — don’t abandon them

Male–female comparisons are powerful in biomedical research — don’t abandon them

Clinicians and researchers must also talk more to people living with schizophrenia, whose experiences and perspectives can offer invaluable insights into priorities for research and treatment. Such conversations have already revealed, for instance, a need to better understand and treat some of the symptoms that are not helped by current therapies, including low attention span and memory or social problems (see K. Landolt et al. Psychol. Med. 42, 1461–1473; 2012).

Examples of good practice can serve as templates for others. One is the United Kingdom’s early intervention in psychosis programme, in which multidisciplinary teams of mental-health professionals focus on listening to individuals when symptoms of psychosis first appear, and working collaboratively with them to craft holistic treatment plans according to their needs. And, at the University of Barcelona, researcher and nurse Antonio Moreno-Poyato and his group provide a private therapy space for people with mental-health disorders hospitalized in health-care units. The rooms are designed to establish bonds of trust between nurses and individuals affected by these conditions, to enable the two parties to collectively agree on objectives and interventions (see A. R. Moreno-Poyato et al. Int. J. Mental Health Nurs. 30, 783–797; 2021).

Greater investment from governments is essential, as are education and public-awareness efforts. My father sometimes shouted at people in the street, and passers-by would stare and scold. If they had known more about schizophrenia, he might have been met with compassion, instead. Public campaigns could highlight, for example, that schizophrenia can often lead to homelessness, because of society’s inability to care for people with the condition.

Through all these steps, researchers, health-care workers and those affected by schizophrenia, including families and carers, can increase the visibility of this disorder. I hope that this will exert pressure on governments to increase financial support, and give as many people as possible the help that my father needed but could not find.

Nature 630, 531 (2024)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-02024-1

Reprints and permissions

The author declares no competing interests.

Personalized profiles for disease risk must capture all facets of health

Personalized profiles for disease risk must capture all facets of health

Male–female comparisons are powerful in biomedical research — don’t abandon them

Male–female comparisons are powerful in biomedical research — don’t abandon them

How paediatrician researchers are advancing child health

How paediatrician researchers are advancing child health

Psychedelic research and the real world

Psychedelic research and the real world

A concerted neuron–astrocyte program declines in ageing and schizophrenia

Article

Brain growth charts, discovery gap — the week in infographics

News

Genetic origins of schizophrenia find common ground

News & Views

Establish a global day to tackle postpartum haemorrhage

Correspondence

Could rats and dogs detect disease better than the finest lab equipment?

Outlook

How climate change is hitting Europe: three graphics reveal health impacts

News

AI machine translation tools must be taught cultural differences too

Correspondence

Large-scale neurophysiology and single-cell profiling in human neuroscience

Perspective

Human neuroscience is entering a new era — it mustn’t forget its human dimension

Editorial

The wide-ranging expertise drawing from technical, engineering or science professions…

Shenzhen,China

Shenzhen Institute of Synthetic Biology

Call for top experts and scholars in the field of science and technology.

Shenyang, Liaoning, China

Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University

We aim to foster cutting-edge scientific and technological advancements in the field of molecular tissue biology at the single-cell level.

Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

Guangzhou Institutes of Biomedicine and Health(GIBH), Chinese Academy of Sciences

Dallas, Texas (US)

The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (UT Southwestern Medical Center)

Postdoc positions on ERC projects – cellular stress responses, proteostasis and autophagy

Frankfurt am Main, Hessen (DE)

Goethe University (GU) Frankfurt am Main – Institute of Molecular Systems Medicine

You have full access to this article via your institution.

Personalized profiles for disease risk must capture all facets of health

Personalized profiles for disease risk must capture all facets of health

Male–female comparisons are powerful in biomedical research — don’t abandon them

Male–female comparisons are powerful in biomedical research — don’t abandon them

How paediatrician researchers are advancing child health

How paediatrician researchers are advancing child health

Psychedelic research and the real world

Psychedelic research and the real world

An essential round-up of science news, opinion and analysis, delivered to your inbox every weekday.

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

© 2024 Springer Nature Limited